Mineral Rights

In the United States, oil and gas rights may be owned by private landowners, states, the federal government and Indian tribes. These rights are considered mineral rights and extend underground from the property boundaries of the landowner to the center of the Earth. In the United States, unlike in many other nations, there is widespread private ownership of mineral rights.

Mineral rights may be separated from other property rights, such as surface ownership, through different methods. A mineral owner may sell or convey the surface while retaining the mineral rights or vice a versa. When different parties own the surface rights and subsurface (mineral) rights, it is referred to as a split or severed estate.

When a split estate situation occurs, the mineral estate is the dominant estate and mineral development takes precedence over surface rights. This status is based on significant case law, which, specifically provides, that mineral owners have the right to enter and use the surface of leased lands to exploit mineral resources. Until recently, payments to surface owners were routinely restricted to crop damage, loss of grazing or damage to an improved structure. This approach has changed over time and more states follow the concept of reasonable accommodation where operators must reasonably accommodate the surface owners use of their lands. The level of accommodation required varies from state to state with some still focusing on the surface estate being subservient and other states requiring surface owner consultation regarding placements of equipment and timing of oil and gas activities, negotiated surface use agreements or a state may have a separate surface use permitting process.

When purchasing property, it is always wise to determine ownership of mineral rights.

Mineral Law

Two different laws govern the development of oil and gas mineral rights, depending on the state. One is the rule of capture and the second is based on the concept of correlative rights.

The rule of capture provides that any fluids that flow into a well, on land of which an operator has mineral rights, are the property of that operator, regardless of where the oil and gas originated. In the early days of the oil and gas industry, under the rule of capture, people considered oil and gas to be owned by whoever brought it to the surface first. This encouraged oil and gas development, but also frequently resulted in a push to drill and complete as many wells as possible and to pump them aggressively before someone else captured the hydrocarbons. This led to oil fields that looked like the one below and resulted in damage to historic reservoirs.

The second law or doctrine is a more complex system in which oil and gas rights are proportional to the total amount of land leased or owned. Therefore, each mineral owner is afforded their fair share of the recoverable oil or gas beneath his or her land. This concept was recognized by courts and state agencies regulating oil and gas, and the concept of “correlative rights” was developed. The implementation of the correlative rights doctrine continues to promote oil and gas development but requires operators, in a specific oil and gas producing formation, to manage the formation in manner that reduces excessive drilling and production, limits damage to common reservoirs, and protects correlative rights of the mineral owners.

Drilling and Spacing Units

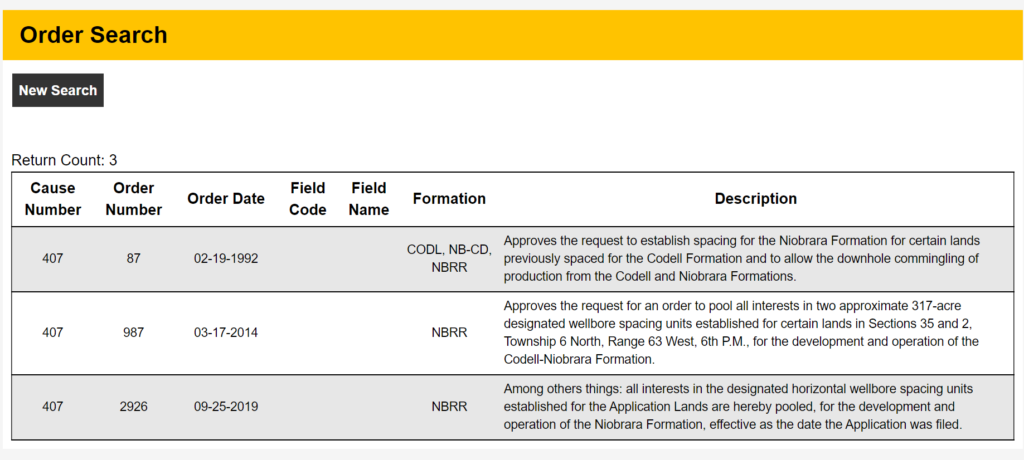

Regulatory agencies, which play a significant role in managing issues regarding the rule of capture and the protection of correlative rights, have developed rules and regulations to ensure the most efficient production of an oil and gas formation or horizon. These include the development of drilling units, imposing well spacing orders, and establishing pooling requirements.

A drilling and spacing unit is the maximum area in a pool which may be drained efficiently by one well to produce the maximum recoverable oil or gas in such area. Based on reservoir and geologic data operators may request down spacing of a unit to allow additional wells to be drilled to ensure the resource is not stranded. For instance, operators may request to down space to 20 acre or even10 acre spacing.

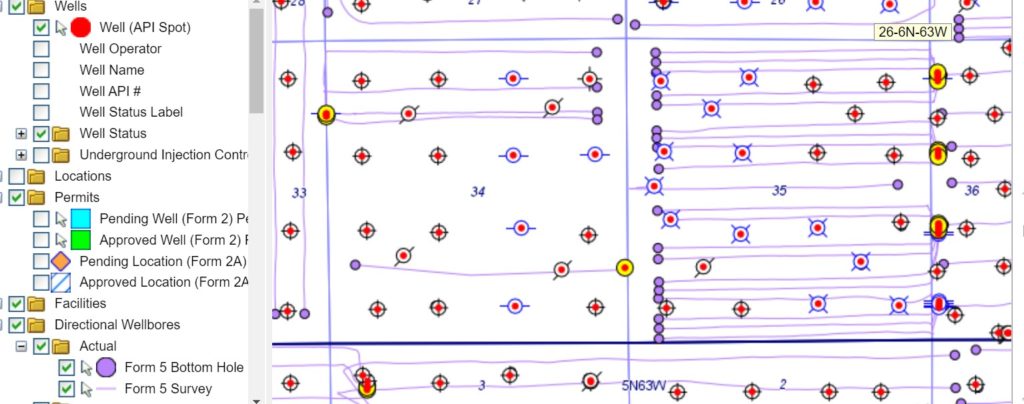

Well spacing specifies the distance a well can be from other wells and the boundaries of the lease on which the well is drilled. For example, in Mississippi the statewide standard for well spacing requires wells to be at least 1200 feet from any other well producing from the same horizon, and that no well may be located less than 467 feet from the boundaries of the lease on which the well is drilled. This set up a drilling pattern requiring 40 acres around each well. Well spacing can be developed on a statewide basis or specific to an area or field. Spacing rules allow one well per formation so if there are several producing formations this might result in additional wells in the 40 acres. The purpose of statewide well spacing and field rules is to promote the regular development of oil and gas and the protection of correlative rights.

More complex well spacing and drilling and spacing units may be created based on reservoir characteristics, drilling techniques or even a regional concern. As an example, the two sections in Figure 4-3 include a special area (Greater Wattenberg) with well spacing designed to accommodate agricultural activities. It was effective for vertical drilling but with shale development and horizontal drilling operators requested larger and more complex drilling and spacing units.

Greater Wattenberg Area (“GWA”): In the GWA Special Area located in the DJ basin, operators may utilize the following described surface drilling locations to drill…. or recomplete a well:

(1) A square with sides four hundred (400) feet in length, the center of which is the center of any governmental quarter-quarter section (“400′ window”); and,

(2) A square with sides eight hundred (800) feet in length, the center of which is the center of any governmental quarter section (“800′ window”).

The GWA spacing was initially used for vertical or directional wells which are now routinely being plugged and abandoned to make way for long horizontal laterals drilled in larger more complex drilling and spacing units.

Pooling

During the pooling process, extraction companies buy or lease mineral rights from multiple landowners and ‘pool’ them to form a drilling unit upon which they can legally place a drill rig.

Compulsory Pooling

Compulsory (also known as forced, statutory, jurisdictional or mandatory pooling) forces landowners, which do not want to lease their minerals for extraction, into a drilling unit. Generally, forced pooling does not provide surface access to the non-consenting landowner’s property but does allow drilling to occur underneath their land, while compensating the owner for the extracted resource.

The Lease Process

In the United States a mineral lease is a private legal contract between the mineral owner and the operator. The goal of the leasing process is to produce an agreement between a property owner and an operator in which mineral rights are leased in exchange for a recurring rental payment and royalties from any oil or gas produced on the land. A landman typically represents the operator and approaches the mineral owner directly to begin lease negotiations. The leasing process is not regulated by a state or federal agency unless it involves federal minerals.

Due to the complex nature of the leasing process, the mineral owner may want to retain an attorney with specific oil and gas leasing expertise to assess the contract before it is signed.

The Nuts and Bolts of a Lease

A mineral lease is a contract under which an entity leases the mineral rights for the purpose of developing oil and gas. Leases can be simple or extremely complex; however, there are basic components found in most leases. Let’s look at some of the basic components that make up a mineral lease.

Parties

The lease will contain the date the lease was executed and define the parties involved. The mineral estate owner is the lessor and the party receiving the lease is the lessee.

Timing and Payment

A lease gives the lessee (operator) rights to explore for and extract oil and gas on the land owned by the lessor. The lease will include a primary term, during which operators make yearly rental payments. The primary term is commonly in force for five to 10 years. If the operator does not begin production during the primary term the lease expires unless it is extended by what is termed a delay rental. Delay rentals allow the lease to be extended, usually at the discretion of the lessor.

The lease will also have a secondary term that allows the oil and gas company to continue producing oil and gas beyond the term of years specified in the primary term, so long as production is active, or it may state as long as production is in commercial or paying quantities.

If oil and gas production begins during the term of the lease, rental payments stop and are replaced by royalty payments. A royalty payment is the fraction of the total value of all oil and gas produced from the well to be paid to the lessor and is a key component of the lease. Royalties typically ranges from ⅛ to ⅙ of the total value of the hydrocarbons extracted. Royalties are not affected by the profit margins or cost of oil or gas production, which in most cases are absorbed by the operator. Royalty payments continue for the productive life of the well.

Terms to protect landowner

In addition to the basic financial terms of the lease, there are typically numerous measures to protect landowners (landowners often hire lawyers to ensure that they are adequately protected by the lease).

For example, an operator may be required to post a bond or otherwise guarantee financial reimbursement to property damage caused by operations. Additional financial penalties may be invoked if the terms of the lease are violated.

To discourage operators from shutting in wells until economic conditions are more favorable, most leases include terms that charge operators rental fees for shut-in wells.

If the operator violates the lease or decides to abandon drilling on the site, they are required by the lease to remove all equipment from the site. However, leases often prohibit the removal of equipment until the operator pays all outstanding debts to the landowner.

Additional Terms

Bonus payment: A mineral lease bonus is a one-time payment made to the mineral rights owner when the oil and gas lease is signed. It may be in the mineral lease or may be part of a separate document.

Granting Clause: The clause identifies the oil and gas rights in the lease, the right to develop the oil and gas rights, and describes the piece of real estate, and the activities that can be conducted on the real estate for purposes of exploring for and developing the oil and gas.

Indemnity: This clause protects the landowner in case a claim or suit is asserted against the landowner and/or the landowner incurs some type of liability, loss or damage due to the activities of the oil and gas company.

Audit rights: Allows the landowner to examine, inspect, or audit the books, records, and accounts of the oil and gas company

Default clause: Specifies the circumstances under which a landowner can claim that the operator has defaulted or may provide information on how to terminate the oil and gas lease.

Force Majeure: This clause may allow the lease to be extended due to certain acts or occurrences, such as acts of God, adverse weather conditions, strikes, riots, or other occurrences that may be specified.

Domestic gas: A landowner may negotiate terms to receive free gas from a natural gas well for personal use, such as home heating.

Surface: Most leases set out requirements for site restoration. Although restoration is often required by oil and gas regulations, including additional terms in the lease guarantees that the landowner has the power to force operators to complete restoration in a timely manner.

What a lease doesn’t do

One thing that a lease does not do is single-handedly give operators permission to drill. Although the landowner may support drilling, it is usually the state agency that regulates the oil and gas industry that has the ultimate authority to approval drilling. Most agencies grant the authority to drill through a permitting process.

The permitting process is one of the most important steps to ensuring responsible development of oil and gas resources. We will focus on the permitting process for the remainder of this section.

Images: “Example Oil and Gas Lease” by Top Energy Training