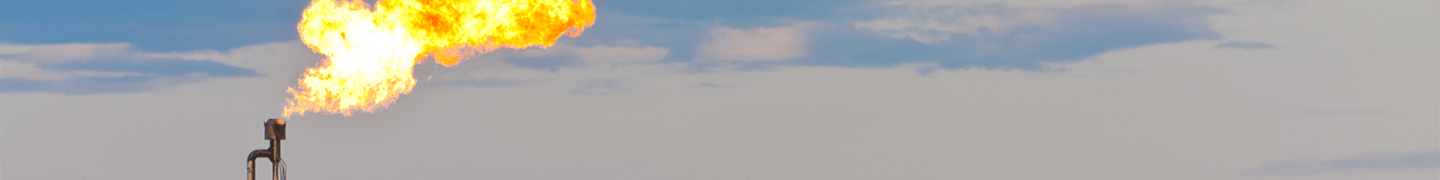

One of the most recognizable and memorable images of the oil and gas industry is a tall flare stack burning with a visible flame. The fuel for combustion is natural gas, which is a valuable commodity that oil and gas operators sell on the market for revenue. While more economical to capture and sell natural gas, gas flaring has its own role in oil and gas operations. For example, if the production site is isolated from a pipeline infrastructure to collect and transport the natural gas, then operators will usually flare any natural gas associated with oil production. However, before production steadies, operators have several other reasons for flaring natural gas.

After operators drill a natural gas well or drill and fracture an unconventional well, they test the pressure, flow and composition of the hydrocarbons produced by that well. During this process, operators use flaring on the site until the flow has stabilized, which may take days or weeks.

During production, when production rates exceed the recommended pressures of equipment or pipelines, special emergency release valves channel natural gas to flare stacks for flaring. These precautions allow operators to regain control of the production flow safely without over pressurizing equipment.

During processing and compression of natural gas for sale or storage, it runs through several units to scrub water and other undesirable compounds from the gas. Some units capture waste gas and return it to the system for processing, but in some scenarios where this is not possible, flares on specific equipment burn off gas vapors.

Previously, we outlined the difference between carbon dioxide and methane in terms of global warming potential. Combustion at the flare stack turns methane into carbon dioxide rather than emitting methane directly to the atmosphere. This presents an environmental benefit to flaring. Also, because methane is a combustible gas unlike carbon dioxide, emissions of methane are at risk of catching fire. Unidentified fugitive methane emissions may combust if they encounter an open flame or spark on site. Likewise, if operators vent methane directly to the atmosphere or allow equipment to over pressurize rather than using a flare stack to combust natural gas, they increase the site-wide risk of explosion and fires.

Concerns about flaring are similar to the concerns of all combustion. The flames from flare stacks are very bright and can stretch many feet into the air depending on the rate of release. Large swaths of flares in the Bakken Shale region of North Dakota and of the Eagle Ford Shale region of Texas can be seen from space. Also, depending on the volume and velocity of gas passing through the flare stack, combustion can be quite loud. This is a growing problem in urban production areas where flaring can occur around the clock, disturbing operators’ neighbors.

Images: “Oil gas flare” by Glovatskiy via Shutterstock; “Natural gas flare, Karnes City, Texas” by Jeffrey M. Phillips, The University of Texas