One of the most common reasons for tripping out of the borehole is to run, set, and cement casing in the well. In these cases, the trips are part of the drilling plan for the well. Each time the drill reaches the depth at which a new casing is to be set, drilling stops and the casing process begins.

Setting and cementing casing is one of the most important parts of the drilling process from a regulatory perspective. In the following video, we’ll learn why.

Transcript

Wellheads – Paul Bommer – The University of Texas at Austin

Let’s talk about the wellhead, a critical piece of every well that controls surface flow and suspends the casing strings placed in the well.

It’s something that needs to be constructed carefully and correctly every time. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with an oil or gas well, but the worst kind of wrong has to do with failures of the wellhead.

What we call the wellhead is actually a group of steel devices that work together and are firmly attached to one another during the course of drilling a well.

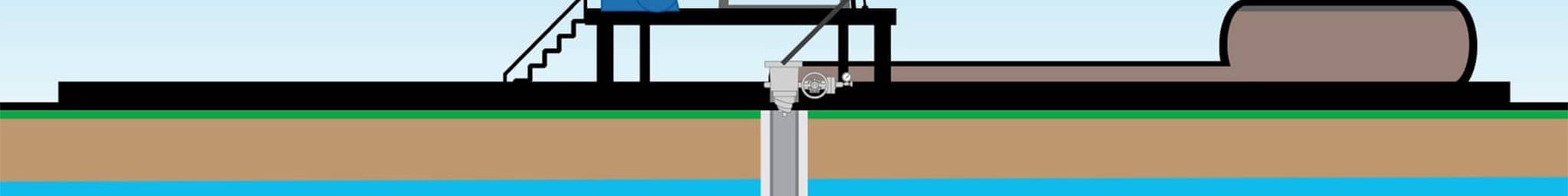

A wellhead can be built modularly or it can be more or less one piece. The wellhead must be anchored and sealed in the ground. This is done by attaching it to the top of the surface casing.

The surface casing is large diameter steel pipe that has been cemented in the ground with the cement filling the annular space outside the casing all the way back to the surface. This is extremely important because the surface casing becomes the anchor point and the external seal for all of the wellhead equipment plus any other pipe that is placed in the well.

The surface casing must be large enough inside to allow for the passage of the largest bit that is required to drill the next section of the well. It must be set deep enough to protect the shallow usable quality water-bearing formations.

As a general rule of thumb surface casing must be set 100 feet deeper than the deepest usable water formation. It also must be deep enough to insure that any pressure from deeper layers cannot breach around the outside of the surface casing and escape at the surface.

Let me reiterate, the surface casing must be cemented all the way back to the surface. Subsequent casing strings may not need to be cemented all the way back to the surface, but they need to be cemented far enough to create a good external pressure seal.

As a general rule of thumb 1,000 feet of cement is considered the minimum distance to provide a seal and prevent a pathway for fluid flow to the surface.

The first piece of the well head is installed on top of the surface casing. On shore this is called the Braden head which is simply a flange with an outlet underneath that provides a place to bolt on the next segment and a bowl inside in which to suspend or hang the next casing string. In deep water where the wellhead will be placed on the ocean floor it is called the high pressure connector.

During drilling and completion operations, blowout preventers are placed on top of the Braden head.

If I need to use the blowout preventers, I intend to close them and if I close them, I could easily trap pressure from the reservoir inside the well and if I don’t have a good enough competent cement seal around each of these strings, the blowout preventer is not going to stop a blowout because again I’ve got a pathway out.

In a worst case scenario, say during a high-pressure fracking job, the entire wellhead could be ejected from the top of the well due to downhole pressure if the seal is not firm.

This has happened. So the cementation of the surface casing is something everybody should be interested in. It’s also one of the things that regulators are often called upon to witness.

After the well has been drilled, it may be necessary to run and cement another string of casing called intermediate casing. The purpose of this string is to seal the exposed well-bore for high pressure zones yet to be drilled.

This string of casing is landed and sealed at the top in the bowl of the Braden head. Another piece of wellhead equipment is installed on top of the Braden head and it is called the intermediate spool. The blowout preventers go on top of this part of the wellhead so the well can be safely drilled deeper.

Some wellheads, like the high pressure connector used on the ocean floor, have enough space machined inside to hang a number of different casing strings without disturbing the blowout preventers.

When the well reaches the final depth it is possible that a final string of casing called production casing will be run and cemented in place.

The top of the production casing is hung and sealed in the bowl of the intermediate spool or the high pressure connector. Now the blowout preventers can be removed and the last pieces of the wellhead installed.

These together are the tubing head which will hang and seal the top of the production tubing up which the reservoir fluids will be flowed to the surface, and the upper tree assembly, sometimes called the Christmas Tree. The Christmas Tree has the master valves that are used to shut in a well and the flow control choke that is used to regulate the flow out of the well.

Similar wellhead equipment is installed on top of the high pressure connector for subsea completions.

The upper tree assembly can be exposed to high pressures during the production of fluids and during the fracturing jobs that are done on many wells today. The upper tree assembly must not fail or an uncontrolled flow can result – as has happened – in a small number of wells.

Casing Regulation Variability

Dr. Bommer mentions that surface casing must be 100 feet deeper than the deepest usable water formation. This is true in his home state of Texas. Other states set their own regulations concerning the depth of surface casing and they vary from state to state, with some states using 50 feet below the deepest usable water and others using 120 feet below as their minimal distances for mandatory surface casing.

Most wells contain three or more sections of casing:

- The conductor casing lines the very top of the well, and serves to prevent unconsolidated materials found at the surface from collapsing into the well, as well as allow the drilling fluid in the borehole to be “conducted” up to the steel mud pits.

- The surface casing lines the wellbore from the surface to a location past the bottom edge of the lowest aquifer unit and is the anchor for the other casing strings and BOPE.

- Intermediate casing (sometimes called “protective” or “drilling” casing) runs from the inside the other casings as needed to cover up high and/or low pressure formations and/or troublesome formations such as salt zones and sloughing shales.

- Production casing is used in some wells to line the part of the well that passes through the producing zone. In open hole completions, which we’ll discuss later, the production casing is omitted.

- A liner is any casing string that does not terminate at the surface. These can be intermediate or production liners. There is no such thing as a surface liner.

- A casing string that is run from a liner top downhole back to the surface is called a “tieback” because it ties-back the liner to the surface.

Each length of casing is lowered through the inside of the previously run casing which means that the new casing diameter must be smaller in deeper casing sections. There is something called expandable casing which can be, as the name implies, expanded after running through other casing; but, it is rarely used.

Casing is lowered into the hole by the primary hoisting systems of the rig. Centralizers, which are either bow springs or solid ridges, are attached to the outside of the casing to ensure that it remains in the center of the hole. This ensures that the cement completely surrounds the casing as it circulates up the annulus. This centralization is challenging to get in horizontal sections of a borehole as the casing tends to lie to the low side of the borehole.

Once the casing has reached the desired depth, the top is hung from the wellhead using a casing hanger, which is essentially a flanged pipe or wedge that fits into the top of existing casing or the wellhead.

It’s now time to cement the casing.

Although the ultimate goal is to fill the annulus around the well casing with cement, cement is actually pumped through the inside of the casing, in the same way that drilling mud passes through the drill string before rising through the annulus.

Since drillers don’t want to end up with the inside of the casing being filled with cement, they carefully calculate how much cement will be needed to fill the annulus. After that amount has been pumped into the casing, a wiper plug is inserted into the pipe, followed by drilling mud or water. This plug, which works like the plunger in a hypodermic needle, cleans the cement from the inside of the casing and displaces it out of the bottom of the casing into the annulus. At the end of the process, the casing is filled with water or drilling mud and the annulus is filled with cement up to some point called the top-of-cement (TOC). For surface casing, this is required to be the surface. In other strings, the TOC depends on engineering, geological, and regulatory requirements.

When the cement has hydrated into a solid and the cement job has been checked for proper 360-degree bonding for the entire length of the casing, the wiper plug will be drilled out of the bottom of the pipe and drilling can continue.

Images: “Drilling Completion Illustration” by Top Energy Training